When the pandemic first hit in March 2020 and my office shut down, and everyone was scared to go outside, when a vaccine hadn’t been discovered yet and the retail shops and restaurants all had closed — with one diner and two coffeehouses in my neighborhood now permanently shuttered — I had no choice but to cook. I had to feed my family. I had to keep myself occupied, “busy” being my default way to cope.

Cooking became a way to exert control in a world that, overnight, morphed into a Twilight Zone episode. While other people drank more alcohol or gained 30 pounds or drove their pickups and SUVs faster, I knit scarves for friends and family members, discovered new streaming services. And cooked.

Red lentil soup from a Beth Dooley recipe in the “Taste” section of my local newspaper, a consistently reliable source of recipes. Sweet potato-apple stew from the New York Times cooking app (the most creative bottom line–builder a national news organization has discovered). Chicken wild rice soup from an amalgamation of recipes in a 20-year-old cookbook that parents at Greenvale Elementary School compiled and sold as a fundraiser when my younger son was there.

Now, as we face down the third or fourth variant in the third or fourth year of COVID-19, bars and restaurants are open again. Coffeehouses are crowded. And I am still cooking, this time because inflation has me earning less in real dollars than I have in years.

Although I have two dozen cookbooks, a recipe box with index cards from the 1980s, a drawer full of torn out recipes that I swear I’ll sort one day and that veritable New York Times cooking app, well worth the $40 annual fee, I turn most often to the white, three-ring notebook that I began assembling during those first weeks of the pandemic.

At 65, I am creating a newfangled version of an old-fashioned cookbook and finally teaching myself — trusting myself — to cook.

Cooking is an act of showing up in the world, of caring for ourselves and for others.

Beth Dooley, The Perennial Kitchen

My younger son has grown up to be body conscious, like I am — particular and intentional about what he eats. My older son, a weightlifter, seems perpetually pleased to be offered food. “Are you hungry?” has become my default greeting when he stops by.

Cooking and baking are gifts, meant to be shared. I keep homemade muffins on hand during the winter so I can thank the neighbor across the street when he clears our driveway with his snowblower. I dropped off a package of bars to the neighbor behind us as a small “thank you” for hosting a backyard gathering with homemade carrot cake, complete with sugared carrot shavings, to celebrate my 65th birthday on July 4. When I make beef stew in the crockpot with extra vegetables and more seitan than stew meat, I always package up a big serving for my younger son.

My father was an attorney, and I remember my mother hosting dinner parties for his clients, “back when lawyers couldn’t advertise,” she liked to say. Beef stroganoff and duck with orange sauce were two favorite entrées. We kids would gather at the top of the stairs and sometimes sneak down for treats: bowls of salted mixed nuts, relish trays with olives and sliced radishes and tiny pickles, strawberry sauce made with berries from my father’s garden served over cheese blintzes from the Lincoln Del.

Those are happy memories, tinged with nostalgia and regret, from the years before my parents’ marriage fell apart in the early 1970s. My mother lost interest in being either a wife or a housewife and quit cooking, deeming it — incorrectly, I believe — as one of the societal norms oppressing women. I was a teenager then, living at home, and still wince at her embrace of Hamburger Helper, Jell-O with canned fruit cocktail and other convenience foods marketed as liberation, in keeping with the times.

If you can read, you can cook, the saying goes. And that’s how I started:

- Reading recipes, especially in the venerable Betty Crocker Cookbook.

- Following directions on packages of Kraft Macaroni & Cheese.

- Gingerly using spices, based on whether I liked their smell.

Eventually I became a mother, in my early 30s, and had to learn to cook for kids. I dubbed myself a “housewife cook” back in those busy, money-conscious years — fully invested in my career but anxious also to be a Mom. Relying on advice from the likes of Working Mother magazine, I hid shredded carrots in spaghetti for extra nutrition, engaged the boys at my elbow when I baked banana muffins so they would be invested in the outcome, made grilled cheese sandwiches in a specially coated pan so the bread would turn a perfect golden brown.

Being a housewife cook means making do with what’s on hand, experimenting with ingredients that might go together, never creating a dish the same way twice. It’s the “no-recipe recipes” now made famous by Sam Sifton in New York Times Cooking, encouraging people “to improvise in the kitchen” and be less bound to precisely written recipes.

Leave it to a man to monetize a practice that women have been engaging in for years. “My grandmother, like many of her generation, was famous for the pseudo-recipe, a little of this, maybe some of that,” explains my sister-in-law Nicole, herself an accomplished cook. “Even the handwritten cards are near impossible to use to replicate anything without trial and error.”

That’s why old women make the best cooks — and conversationalists. Time has taught us the value of being fearless.

Cook a recipe once and you’re playing a cover song. Cook it four or five times, though, and you’re playing a new arrangement.

Sam Sifton, New York Times

As an old woman now myself, I’ve learned that experimentation in the kitchen is often worth the risk, and way cheaper than eating in restaurants. You put apples in the steel cut oatmeal because you need to use them up or chopped kale in the wild rice soup to justify the butter and whole milk that render it creamy and delicious. Preparing an egg dish for Sunday brunch means reviewing a recipe and the contents of the fridge, and then vamping. No cottage cheese on hand? Try ricotta, and it works!

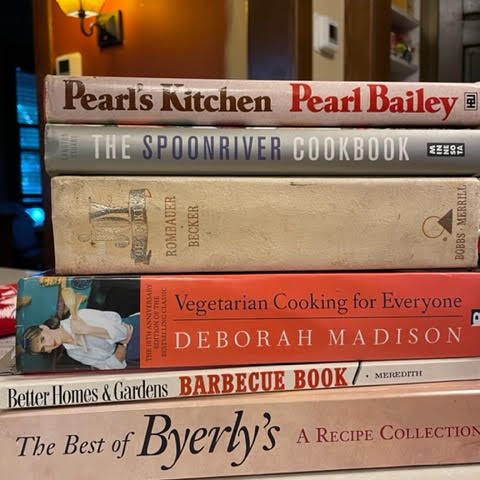

That’s why I am creating my three-ring-binder cookbook, with printed recipes in plastic sleeves, to capture the improvisations that have made recipes my own. Even so, I leave room to write notes for ongoing adjustments and adaptations, much like The Best of Byerly’s cookbook full of neat, penciled notations I found at a library sale. That the Byerly’s cookbook is now online is more convenient, but a digital version will never tell me that Parmesan Dijon Chicken is “easy” and “very good” or that the cayenne pepper in the Shrimp Creole should be cut back.

“I don’t consider cookbooks as static things,” said a reader recently in an online discussion in Carolyn Hax’s intelligent advice column in the Washington Post. “In my mind they are meant to be notated, spilled on, dog eared.”

When I asked my siblings about their own use of recipes, my sister Debbie pointed me toward a piece in The Atlantic sharply critical of Sam Sifton’s “no-recipe recipes” trend. In “When Did Following Recipes Become a Personal Failure,” from April 2021, writer Laura Shapiro claims that Sifton’s call to “make the act of cooking fun” recreates the Happy Housewife stereotype that duped middle-class white women of my mother’s era.

Sure, I can call myself a “housewife” cook because I never was a housewife. But I can enjoy the creativity and selflessness of putting together meals in my kitchen not only because I want to eat good tasting, healthful food but because I want others to enjoy it, too. Nothing about that threatens the feminist or careerist mindsets that have defined me.

I like the efficiency of managing a kitchen. Cooking, grocery shopping, putting my hands in sudsy water make me feel safe, make my life feel ordered, help me stay on top of the chaos that COVID and rising crime rates and visible climate change induce. Cooking and sharing food connects me with generations of women — my stepmother, Dorothy, my Aunt Mary, my sister-in-law Peggy, all of them gone — who cooked for me and my family, who opened their kitchens in all their messy, miraculous, sometimes maddening glory. And who, in the process, showed me their humanity. And their heart.