Catherine Spaeth lives in an 1894-era house with a wraparound front porch, carved oak banisters, an abundance of natural light and a high-ceilinged kitchen that suits her latest adventure — a pastry and baking certificate from Saint Paul College that she hopes to parlay into a part-time job or a small catering business.

In addition to the chance to perfect her baking skills, she likes the certificate’s emphasis on classes like “Food Safety and Sanitation” and “Culinary Nutrition Theory.” Her recently resurrected blog, The Butter Chronicles, features posts about how food choices affect our brains, the rise in U.S. sugar consumption and why professional cooks never wipe their hands on their aprons.

At 63, Spaeth (below) has run study abroad programs in private higher ed, taught American history and literature, and co-owned a company that designed college cultural immersion programs. She speaks English, French and Italian and holds advanced degrees in American studies. She and her husband, an athletic outdoorsman, took a six-month pilgrimage walk through Europe in 2022.

With a life that expansive, why go back to community college now, cramming to relearn algebra for the admissions exam only to sweat alongside students young enough to be her kids? The why is simple: Because she can. “It’s been really fun,” says Spaeth, over hot tea and homemade scones.

“Going back to school is an incredible luxury,” she acknowledges, though Spaeth balks at the assumption that she “doesn’t have to work.”

“What that conjures up for women is way different than what it conjures up for men,” she explains. “It’s saying, ‘You don’t have to do anything.’ You can stay at home and everything you do at home is not work” — a stereotype and societal perception that drove me, 40 years ago, to pursue a paid career.

Both Spaeth and her husband, a retired lawyer, plan to forego drawing Social Security until they’re 70. “We’re not big spenders,” she notes, “and our mortgage is paid off.” So, her goal in returning to college is less to earn money than to find purpose after decades of full-time work. “I don’t want a life with no commitments,” Spaeth says.

What happens after 60?

Like many professionals in their 60s, including me, Spaeth is on a glidepath toward retirement. Not ready to quit work entirely but situated financially to have options, we have left full-time careers for a variety of reasons:

- We earned and saved enough over the course of our working lives that we could afford this choice.

- Medicare gives us reasonably priced healthcare coverage at age 65 without having to rely on employer-provided benefits.

- We watched as our peers, deemed irrelevant or overpriced, were laid off or restructured out (yes, it happens to people over age 60, despite the legal risks).

- We opted to do something different — volunteer, travel more widely, pursue a passion — when the careers became less relevant to us.

- We have spouses who may be older or are retired themselves.

Glidepath is a financial planning term that references the portfolio rebalancing typically recommended as people get closer to retirement. But it applies to the path that Spaeth and I are pursuing, too: more schooling, in her case; two part-time jobs, in mine.

As a self-described workaholic, I found myself ready to slow down at 65 but not to step away from work entirely. My career has meant too much to me — in identity and intellectual stimulation, in the pride and purpose of supporting a family — to simply flip a switch and say: “I’m done.” Plus, I also want to delay drawing Social Security.

“I love the term glidepath,” says Spaeth, whose study-abroad business ground to a halt once COVID struck. “It was a rough year and a half trying to stay afloat with no revenue coming in.” She calls the pastry and baking certificate her “next project,” one that allows her to look ahead rather than wallowing in the business loss.

That sense of optimism is particularly important as women age. “Part of wanting commitment and engagement is related to an identity,” Spaeth says. “As older women, we’re already invisible in lots of ways, and I don’t want to be out of the world, out of the working world — where, for better or worse, you get your respect or recognition.”

Endings and beginnings

Six months into my own glidepath — a term I prefer to “semi-retirement” — I am learning firsthand about the challenges and benefits of leaving full-time work. The upside of two part-time jobs is apparent in the schedule I have crafted: more volunteering for Planned Parenthood, where I had to operate under the radar while employed by a Catholic university; more opportunities to cook and have people over; more reading and yoga; more coffee and meal dates with my friends and sons.

Still, the expanses of time that I expected to emerge have not materialized. “Busier than I’d like to be” is my standard response when people ask how my new life is going. That’s due in part to my tendency to overbook my calendar.

‘Retired’ is an old word, for men who are leaving manual labor.

Kathy Kelso, St. Paul-based advocate on healthful aging

But it’s also because professional occupations, which my two roles are — managing editor of a Twin Cities–based community blog and executive director of a small, environmentally focused nonprofit — do not lend themselves to hourly contract work.

- Do you charge only for the time you’re at the computer or in meetings? Or is it legitimate to bill for travel time or for processing and “think time,” as another nonprofit executive director encouraged me to do?

- Who pays for networking and professional development, for the outreach that yields relationships more than direct, measurable impact on a given project?

- Most challenging, how do you right-size your ego — your past practice of operating as a doer and decision-maker — so it fits into the box that contract work constructs? When the board differs with your recommendations or does not consult you on a key decision, do you fight it, or recognize that you are not in charge?

The financial definition of glidepath fails to address that emotional turbulence. I am traveling toward a different future, but I lug along my baggage from the past — the habits and ways of working, the belief that my career defined me. I rarely called in sick. I was always pushing for new solutions. I reveled in the résumé-building accomplishments that my career allowed.

None of that matters anymore, because the glidepath leads downhill, to a door labeled “retirement,” which traditionally has meant: That’s it! You’re finished.

Retirement: define your terms

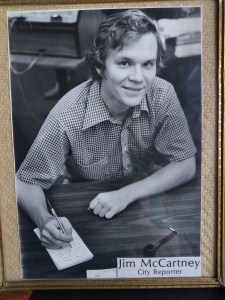

Jim McCartney, 69, a former business reporter and colleague of mine at the St. Paul Pioneer Press, is wary about the term glidepath, given its implication that his career is slowing to a stop. “I’m not necessarily wanting to land,” he says, “if landing means I have to stop writing.”

After leaving journalism for a lucrative career in public relations, McCartney faced a layoff three years ago, at the start of the pandemic. He was 66 and immediately began promoting himself as a writer for hire, even though his wife brings in a full-time income.

“I love writing,” he says. “It’s kind of my identity. I can’t imagine ever stopping writing.”

Unlike me — working at two jobs I enjoy but for significantly less than my full-time compensation, once you factor in benefits — McCartney takes pride in having earned more as a freelancer during the first year after he was laid off. “I don’t necessarily place my self-worth on what I can make, but it’s nice to know that someone is willing to pay well for my services,” he explains. “As long as I like the work, it’s a validation that you’re worth X amount per hour.”

McCartney is now doing business under the moniker JSM Communications LLC, specializing in science, medical and healthcare writing. He will wait until he turns 70 to draw Social Security, subscribing to the common wisdom that “unless you’re really sick and don’t think you’re going to live very long,” it makes sense to maximize the monthly payout from the government.

Two of his close friends from the Pioneer Press are retired and involved in volunteer work at nonprofits, their reporting days behind them. But McCartney, who began his career as a city reporter at the New Ulm Journal (above), likes the word retired even less than he likes glidepath.

“I don’t want someone to think, ‘Oh, I wish Jim were still writing, but he’s retired.’ I don’t want people to think I’m out of the game,” he says, “because I’m not out of the game. I’m still writing, but I’m doing it on my own terms.”