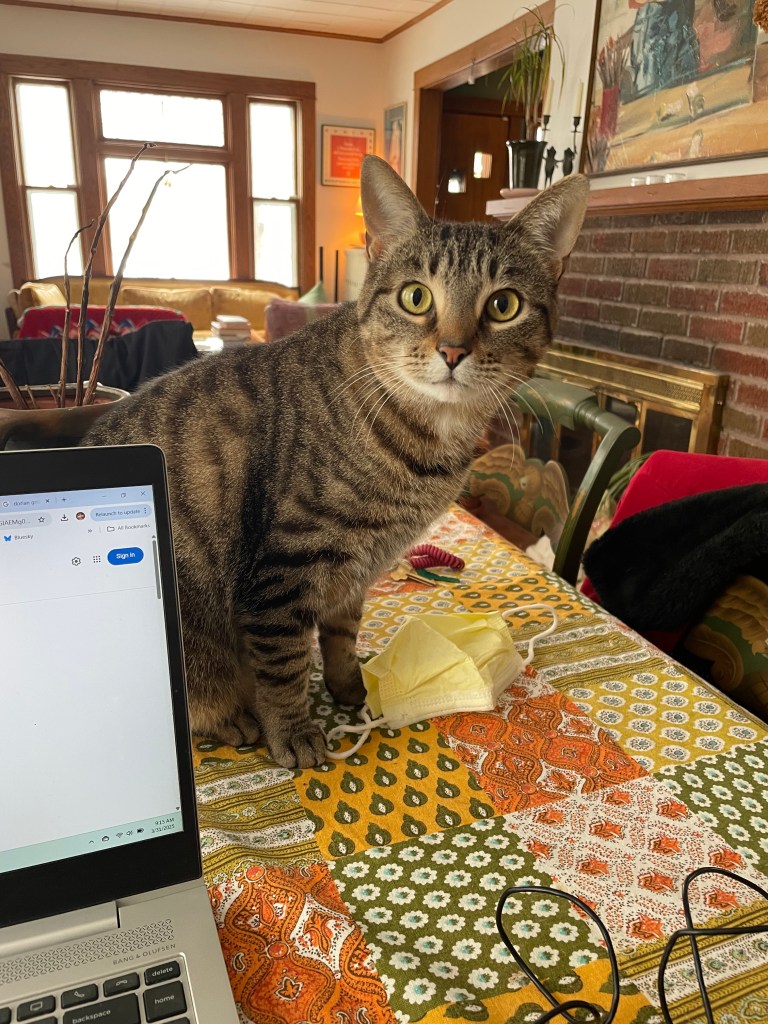

I gained what I thought was going to be temporary custody of a cat last August, when my older son, Sam, left Minneapolis for film school in London. I’m allergic to cats, and after the first of two painful sinus surgeries when I was 33, an ENT specialist told me to get rid of the cat I had and never own another one. But here we are.

The plan was for Q.D. — Quaid Douglas (my son’s riff on the Arnold Schwarzenegger character, Douglas Quaid, in the 1990 version of “Total Recall“) — to stay at our house through the fall, and then my husband, David, would fly the cat to London in early December, when Sam was on break from school.

Months later, after learning how difficult English authorities make it to bring a pet into their country, Q.D. is part of the household. He has navigated a relationship with our two run-the-show dogs, all the more remarkable because Q.D. was born a tripod, with only a flipper for his right front leg. He’s quit running away from David, and now that I have newly prescribed medication for my allergies, I am happy to have him hang with me wherever I am working, cooking, reading or doing yoga (he likes to lick my feet).

Still, as easygoing as Q.D. (sounds like “cutie”) seems to be, I steadfastly remain a dog person. I happily walk Mia and Gabby every morning, whatever the weather. I am comforted when Mia sleeps with me or when either dog shows affection. I find dogs more interesting than cats.

So, when J.D. Vance’s past remarks about “weird” and “miserable” childless cat ladies resurfaced during the last presidential cycle — inspiring an amusing New Yorker cover and accusations of “sexist tropes” — I started wondering: What do people, women especially, see in cats?

The articulate, effusive responses I got to that question revealed a side of friends and colleagues I had never seen. As one woman said: “Cat people do not get asked enough to talk about their cats.”

Cats know their own minds

This theme came up several times, starting with my childhood friend Janey, who recently has had to put down two elderly cats. “They choose you as the owner,” she told me, and I wasn’t sure what that meant until Q.D. started waking me at 5 a.m. to feed him or showing up when I was sitting in the basement to watch TV.

Once he got over losing Sam, Q.D. recognized which member of the household was more likely to feed him, rub his tummy and comb out his Ragdoll fur, and he attached himself to me.

“I admire cats for their independence,” said my sister Debbie, who has four cats, including a former feral cat named Oscar Wild. “I think they see us as living with them, not the other way around, and although they can be affectionate and loyal, their goal is to get me to do what they want.”

That struck me as hyperbole until I realized, some days later, that I had begun to stop every week at an Aldi on my way back from Meals on Wheels because the store carries affordable cans of tuna that the cat will eat. Q.D. likes to go outside early in the morning, and so even if I have work or other chores to do, I now station myself at the table by the back door so I can hear his meow when he wants to come back in.

“You can’t train a cat,” says Alisa from my weekly women’s group, “but you can adjust your lifestyle so that the cat is happy enough that you improve each other’s lives.”

Cats are different from dogs

Though I didn’t request comparisons to dogs, I got a lot of them when I asked folks about why they like cats. Forget Democrats and Republicans, or urban and rural. Society tries to divide us between cat people and dog people, though I carry the traits of both, according to a recent Web MD survey.

“I heard somewhere that the difference between dogs and cats is that dogs are trainable,” Alisa wrote in an elegant ode to her cats. “Dogs are food motivated, they have empathy — they’ll adjust themselves to please you. Adopting a cat is like inviting a wild animal to your home. The correct perspective for this endeavor is to not have expectations.”

My longtime friend Elizabeth is staunchly pro-cat and still grieving the loss of her beloved Lily to cancer. What I perceive to be exuberance in dogs, she finds gross and and over-eager. “Unlike dogs, cats don’t slobber or sniff your crotch or knock you over, behaviors I have never gotten used to in dogs, apologies to dog lovers,” she wrote.

Peggy, a former journalism colleague, has had eight cats — “a long line of cats” — and initially chose them over dogs because they better accommodated her erratic schedule as a young reporter. “My soul cat was Rascal, two cats back,” she explained. “This can happen with cats or dogs — that one pet you link souls with in some not understandable way. He was the kind of cat of whom people say, ‘He’s like a dog.’ Which offers a window into how cats and dogs are stereotyped.”

Like all of the cat lovers I queried, Elizabeth is fascinated by these “regal beasts” and their “lion-ish” qualities to a degree that eludes me, perhaps because Q.D. is a skittish, shy loner. “When people say cats are aloof, I say, yes, they can be,” she said. “But like any pet, they all have their personalities, and the joy of having them as family members is discovering who they are. Dog lovers are correct: Cats are in charge. The only way to bond with them is to respond to them as they wish to be treated.”

I don’t want to work that hard for an animal’s attention. Dogs are blessedly simplistic, which suits my already hectic life. Creatures of habit, they are satisfied with the daily pleasures of evening meals and morning walks. They come to me, rather than requiring me to analyze how we should interact.

Not so with cats. “Being a cat roommate or caregiver honestly feels like a better title than just owner,” says Stina, my colleague at Streets.mn, “and I’m definitely not a cat parent. We are roommates, but she doesn’t clean or pay rent.”

Cats get you through

I didn’t think to ask people why they have pets, but the stories they told me point toward an answer: We enjoy the companionship and loyalty, be it the unconditional love of a dog or the more complicated affections of a cat. Several people described how cats had gotten them through difficult life stages.

Stina, 32, talked about the compromised cat, Stevie, she adopted during her 20s. “I had lost my sense of purpose,” she said. “I was partying a lot and working entirely too much, and I decided to adopt a senior cat to force myself to be home more and slow down. Stevie was missing half her teeth, had some cognitive delays and a gravelly meow. She got me out of my depressive episodes, because I knew that Stevie needed me. My role was to give her the best end-of-life care she could get.”

She has since rescued Cali, a calico cat, whose temper — “hissing, spitting, biting, snarling” — had discouraged potential adopters for four months. Once Stevie, the senior cat, died, Stina decided to take a chance on Cali. It took months, but the cat who initially refused to meet her gaze eventually slept on Stina’s pillow and nestled on her shoulder.

“Maybe it was a trauma bond, maybe we just needed time,” Stina mused. “But in being trusted by her, I learned to trust myself. She taught me that I can be both fiercely independent and soft and cuddly.”

Amity, whom I know from social media, promises on Instagram: “You will see cat pics. Maybe social justice. Or public transit. Mostly cat.” Her cat, jokingly renamed Chad “for my asshole co-worker” during the COVID lockdown, is getting her through a rough patch in her marriage.

“My husband and I are separated, and Chad is here for me all the time now,” Amity said. “I come home from work and my place doesn’t feel empty, because there’s a 12-pound beast at the front door meowing for food. I can’t really explain it; my apartment would feel less like a home without him.”

And then with cats, there’s the matter of convenience. “I’m a dog person from childhood. But with a busy lifestyle, and preferring animals that can largely take care of themselves, I am also a cat person,” wrote Melissa, a committed community activist.

Maybe I don’t have to choose between my dogs and the cat, the animals I know and the one I am still learning. Instead of picking a favorite type of pet, I could allow all three to help me navigate some exciting but scary changes in the year ahead.

“You turn around one day, and you’re old,” I told a colleague, a man barely half my age, as we discussed my difficult decision to leave a part-time job that I have really enjoyed during my post-career period of semi-retirement.

“Your peers are retiring,” I said, “and family obligations — whether an aging husband or a coming grandchild — continue to reshape what will be expected of you.”

My younger son’s baby is due on July 31, and I’ll be leaving the job in August. What a summer it will be! On those days when I feel incompetent, when I’ve forgotten how to calm a screaming infant or can’t differentiate a perennial from a weed in the neglected garden, I can turn to the beings who make me feel needed and loved.

And who maybe will teach me how to play again. To take life (and myself) just a little less seriously.