It isn’t that I never swear. It’s just that shit and fuck and goddamn and all the rest have become so ubiquitous that they’ve lost their ability to stun or shock, which, to my mind, is the whole point of swearing.

There are swear words, like the ones just mentioned, and there is crude or offensive language, and all of it seems subjective and so very public these days. On a bus ride recently to downtown St. Paul, a woman started swearing a blue streak into her phone as another man and I were exiting the bus to participate in a City Council meeting. Amid audible shouts of “Fuck this” and “fuck that,” I said to him: “This is why people are uncomfortable on mass transit.”

No one swore giving testimony at the City Council, except to say “damn” once. Clean language was a sign of respect. We know that swearing has its place, and it’s not in front of public officials whom you are asking to vote yes on your pet issue.

The older I get, the less natural that profanity sounds in my speech, as though I’m trying to sound younger, with it, more relevant than I really am — like putting on an outfit from the 1980s that still fits but no longer suits me.

A study reported on CNN Health shows that people who do swear may be more intelligent and creative, have a useful tool to control pain and are less likely to physically strike out when angered. If that’s true, then why is our society so fractured?

Because other studies from the same period, sometime in 2021, say swearing is on the rise, especially since the pandemic; and I know few people whose mental health has improved since then.

The C-Word

The call came in on a weekend, as they usually did. This time, it was a Saturday afternoon. Everyone in the neighborhood had access to my cellphone number, so I wasn’t surprised that the caller was a woman I had never met.

She had been dog-walking, she told me, across the street from the private-university campus where I worked, near single-family houses that had been given over to student rentals. That meant beer cans and weeds in the once tended yards, sagging and smelly couches on porches, and, on this late October afternoon, carved pumpkins lining the steps that led to the front door of a student house.

The word cunt was carved conspicuously, in capital letters, in one jack-o’-lantern where the teeth should have been in the grinning mouth. The woman said she could read it from the sidewalk. Based on the audible indignation in her voice, I took her to be about my age and stage — a product of a time when women’s liberation, as it was called then, sustained and shaped us.

Yes, I assured her, the C-word offended me, too.

As director of neighborhood relations at the university, I handled infractions and misbehavior among students who lived in the quiet residential blocks that surrounded campus. I prided myself on responding promptly and in person. And so, within 10 minutes, I was pounding on the students’ door. Expecting to encounter guys (entitled football players, maybe?), I was surprised to see they were all women.

“This is sexist hate speech,” I told them, after listening to their story of a (likely drunken) pumpkin carving party the night before. They shrugged it off, as did my colleagues in the Dean of Students’ office, who were dealing with the ramifications of what they considered a far more serious offense — the N-word being scrawled that fall semester on a Black student’s residence hall door.

My sons later told me the C-word was part of everyday speech in England and Australia. A female colleague called to gently explain that young women were reclaiming cunt as their own. “I don’t buy it,” I shot back. “They’re participating in their own oppression.” One could argue that Black male comics have reclaimed the N word. That doesn’t mean it should be written on a jack-o’-lantern, in full view of pedestrians — and children — on a public street.

I told her that when I type cunt in a Microsoft Word document, I get a “vocabulary” reminder: This language may be offensive to your reader. What I didn’t say was that the one time a man hurled the C-word at me, he then hurled a gob of spit in my face as well. Luckily, the assault ended there.

“CUNT: An informal name for the vagina. The word was in common use during the Middle Ages and was the name given to a number of streets in various British towns. Parsons Street in Banbury, Oxfordshire was once called Gropecunt Lane.

Urban Dictionary

‘Seven Words You Can Never Say’

We inhabit the speech patterns we heard and learned as children, until we’re old enough to develop and embrace our own. My parents raised my siblings and me to use quiet voices in the library, to address our friends’ parents as “Mr.” or “Mrs.,” a practice I carried into adulthood, and never, ever to swear.

Though I never had my mouth washed out with soap, it was an approved parental practice at the time, much like the paddle for rowdy boys in junior high.

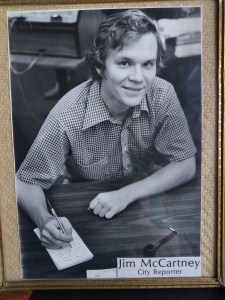

The first time I heard my father use foul language was, oddly, when he was quoted in our small-town newspaper, the Mankato Free Press. He’d been canoeing up north on his annual getaway with the guys, and a fish of some species and considerable size hit my dad’s paddle and landed in the boat. My brother recalls a headline that played on “a real fish story” theme. I was 9 or 10 years old and shocked to read my father quoted in the paper as saying the fish came at them “like a bat out of hell.” I had never heard him swear.

I refused to let my sons say sucks or sucked when they were small, encouraging them to speak more descriptively and expand their vocabulary beyond the vulgar. Both swear liberally now, punctuating their sentences with fuckin’ so often that the word has lost its meaning, or any punch.

I ask why they find it necessary to use fuckin’ as an adjective (“Move your fuckin’ car”) or an adverb (“It was fuckin’ great”). “The concert or the restaurant was great,” spoken with gusto, would convey the same meaning. But this is how their Millennial generation communicates. It’s what they hear on social media and on Ted Lasso (“he’s here, he’s there, he’s every fuckin’ where”) and on countless comedy specials.

That I was raised in an era when comedian George Carlin was arrested for enumerating onstage the “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” seems irrelevant to my grown sons. Nowadays, young adults might concede the seven words as slang, even as vulgarities, but not as swear words.

For the record, here are the seven words as Carlin uttered them in 1972:

- Shit

- Piss

- Fuck

- Cunt (there it is!)

- Cocksucker

- Motherfucker

- Tits.

Two describe private parts of women’s bodies; three are sexual acts, one of which is particularly demeaning (you guess); two are bodily functions. The profanity that people spew so readily these days bothers me not because I’m a prude — though my sons might dispute that — but because I value women in a world that still does not.

Consider how many of these so-called “dirty” terms and phrases denigrate or poke fun at women’s bodies, sexual practices or health habits (yes, a douche bag is a legitimate thing; look it up). And then tell me they are harmless.

“Fuck!”

A friend who is a recognized leader in the abortion rights movement in Minnesota telephoned me on September 18, 2020, to break the news that U.S. Supreme Court Justice and feminist icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg had died. “I wanted you to hear it from me,” my friend said.

We both knew this spelled the end of Roe v. Wade. The president, after all, was Donald Trump.

Among the first people I texted was my sister-in-law in Boston, an attorney who, as a law student, got to meet Ginsburg and hear her speak. She replied immediately and with as much fraught emotion as I was feeling.

“Fuck!” the text read. That said it all.

The full weight of the utterance hit me because I rarely hear her swear. It was powerful punctuation to a moment that began to reshape women’s rights and freedoms as my Baby Boomer generation had known them. That was swearing as it should be: effective, to the point and rare.