The first thing I noticed was the number of women casually wearing blue jeans as they networked, introduced themselves and sipped their morning coffee, as though clothes did not define their role or status.

I had debated what to wear for my first professional women’s conference in over 25 years. Would skirts and blazers still be required? Given that I was taking mass transit to the event, could I get away with athletic shoes? Finally, on a chilly, gray Friday with intermittent showers, I opted for slacks and shoes I could walk in — practical and comfortable. Turns out, I was overdressed!

Between the ages of 36 to 43, I was a full-time newspaper columnist writing about women and work, with a focus on how a generation of middle-class women were navigating the personal and the professional in ways their homemaker mothers never had to do. “On Balance: Issues That Affect Work and Home” the column was called. So, when I heard about the annual women’s conference put on by RSP (Ready. Set. Pivot.) — a Twin Cities-based organization that “guides bold, unapologetic women to their next best thing” — I saw it as a chance to investigate how issues for career women have changed over the past 30 years.

Three conclusions or trends emerged that demonstrate the realities I have recognized in my 60s:

- Progress can be temperamental, and transitory, but movements for social change do push us forward.

- Age shifts our priorities, giving us space to quit dwelling on the inevitable regrets and instead channel them into more authentic ways to lead our lives today.

“Always concentrate on how far you have come, rather than how far you have left to go.”

Heidi Johnson

Trend #1: Finally! Flexibility Is Firm

Back when I was writing the column on women and work (a first for a local newspaper in the 1990s), once- or twice-a-week telecommuting was an almost revolutionary option provided by employers wanting to be seen as work-life friendly and to retain women struggling vainly to “have it all.” I was commuting a long way to the newsroom, with my husband as an at-home parent to our two sons. When a top-tier liberal arts college a mile from home offered me a job in communications, I used it to negotiate a partial work-from-home arrangement.

“Flexibility doesn’t mean working from home on Tuesdays,” a source told me at the time. “True flexibility looks different ways on different days.” And true flexibility, back then, was rare.

Years later, flexibility was among the trends that panelists cited at the RSP conference, organized by former Blue Cross Blue Shield marketing executive Wendy Wiesman, 50, who relishes the “insane freedom” that she gained when she left a prestigious job at a reputable company five years ago.

“Women are more ambitious than ever, and workplace flexibility is fueling them,” says the Women in the Workplace 2023 report by McKinsey & Company, produced annually in partnership with LeanIn.org.

Rather than being the sole exception, as I was, the women I met at the conference treated flexibility as a given rather than a favor that could be taken away. They have the confidence, or perhaps the strength in numbers, to determine how and where they want to work. COVID and a tight labor market have fueled that trend.

I talked with two women in their 40s who are running their own businesses. Diane, a human resources specialist who was often told she “wasn’t typical,” has three children and is the primary breadwinner because her husband is a teacher. Jennifer, who is married with two daughters, lost 100 pounds a decade ago and joined Toastmasters to help her present herself publicly. Now, having tired of working in financial services, she coaches professionals in public speaking.

Wiesman, founder and CEO of Ready. Set. Pivot., says those are the kinds of courageous women her company attracts, who want to design the next stage of their career and leave a secure position if it’s not working. “The DNA is of a woman who is never quite satisfied,” she says. Or, as her website puts it: “The best talent is restless.”

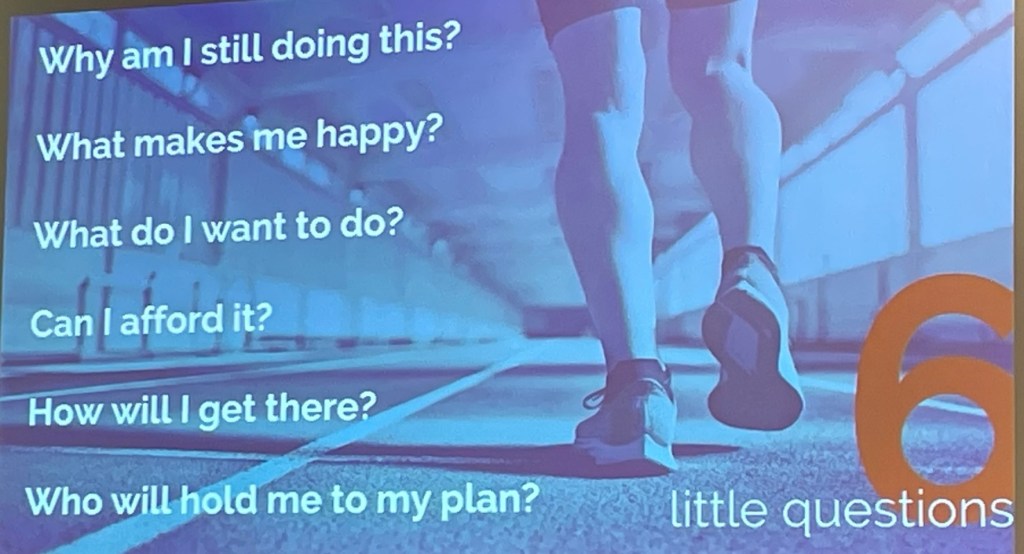

“What does success mean to me now? From the perspective of today, what is most important to me?”

Randi Levin, transitional life strategist

Trend #2: Self-Care Is Not Selfish

As a young business reporter, I interviewed women who wore blue suits to work. Who pulled back their long hair. Who displayed no photos of their children. It’s almost laughable now, how earnestly we tried to blend in with the corporate male establishment (and, of course, it’s the rap against the women’s movement of the 1970s, that we white women of means were merely striving to fit in rather than working to change the system for Black and brown women, too).

Often that meant working harder for less pay and recognition, on the blind faith that someday, it would pay off.

Nowadays, Black women in particular are vocal about the importance — the essentialness — of self-care amid the myriad stressors in their lives. The inaugural “Rest Up Awards,” announced by the Women’s Foundation of Minnesota in September, are granting $10,000 each to 40 nonprofit leaders throughout the state whose organizations are advancing gender and racial justice. All recipients are women of color, according to coverage in the Star Tribune.

“That whole perfectionism thing is out the door,” said the RSP conference’s keynote speaker, Natasha Bowman, a Black attorney, bestselling author and recognized expert on workplace mental health. “Women experience mental health challenges at twice the rate of men, at least. But we women don’t put ourselves on our to-do lists.”

In helping ambitious, hardworking women to design their next phase of life, Wiesman urges them to broaden their focus — and encompass their families, relationships, volunteerism and other interests in a vision of how they want to live. “I first need them not to work 80 hours a week on their day job,” she explains. “It takes a long time to shift out of that. But you have to begin to not over-achieve in that arena. Otherwise, you make no space for the pursuit.”

And you end up in your 60s, as I have, trying to explain your workaholic choices to now-grown children who still resent that you were gone so much while they were growing up.

“I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.”

Maya Angelou

Trend #3: We Get to Be Who We Really Are

In addition to all the jeans and easy laughter at the women’s conference, I noticed that I had never heard “shit” and “fuck” spoken so often or openly at a professional gathering. My age-related aversion to swearing aside, I took it as a brazen symbol of Generation X women’s comfort with themselves. They’re not looking to anyone else to define what is acceptable. “I’m challenging the universe to think differently about talented women,” said Wiesman during her introductory remarks at the event.

Leadership coach Susan Davis-Ali, Ph.D., author of the book How to Become Successful Without Becoming a Man, spoke during a panel discussion about the “great corporate job” she had 15 years ago before leaving to launch her own work and pursue her own path. “Transformation means to change,” she says, including “behavior and attitudes.”

“Getting personal will create risk,” another panelist said. The mostly middle-aged, mostly white women in attendance — exactly the audience for my long-ago business column — heard about negotiating for what they’re worth (“men ask for significantly more money”), about defining what they are offering the market (“generalists aren’t getting noticed; find your sweet spot”) and about speaking with more authority (less “I think” or “I feel”; “own your expertise”).

When a panelist asked how many of us were old enough to have been expected to “be in the office from 9 to 5 with pantyhose on,” I was among the few women who raised my hand. Later, during a breakout session, I spoke up on behalf of my Boomer generation: the ones who blazed a trail but failed to notice that some women weren’t on the path, who overinvested in work as our sole means of self-worth and self-expression.

Wiesman’s generation obviously has learned from our mistakes. “Since the pandemic, women are centering more on their lives and themselves,” she told me. “They’re focusing on themselves first and not the system.”

As a woman of retirement age who still enjoys work, I’d say it’s time to start emulating the women coming up behind us, the ones who declare (as Wiesman’s RSP website says): “This is what I want, this is what I need, this is what I’m good at, this is what I love.” And then get out there and show the world that aging women still have a hell of a lot to offer.