Before we get rolling, understand that my recommendations will apply to older people only if they are physically mobile and relatively fit — and lucky enough to live in a city or community where mass transit is readily available. Being a regular exerciser would be a plus, but what I’m proposing will help people of any age get there.

And my proposal is this: Ditch the car or SUV as often as you reasonably can and commit to trying what we multi-modal enthusiasts call active transportation. That means getting around by foot, bike, bus or train — or some combination of the four — as often as you can.

I use the term “senior” because that is how Metro Transit, my system in the Twin Cities, defines the fare structure for people who are 65 and older. As of January 1 of this year, the bus fare for any senior — call yourself “older,” an “elder” or “young-old,” if you prefer — has dropped to a buck a ride, including during the weekday “rush hours” that COVID rendered almost meaningless.

“We’ve seen travel patterns change,” says Lesley Kandaras, general manager of Metro Transit, who rode every bus and train route during her first year on the job. “We no longer have those weekday peaks of ridership in the early morning and the late afternoon.”

Transit fares includes a transfer window of two and a half hours, meaning I can meet a friend for a leisurely coffee or attend a yoga class and swing by the grocery store afterward and still get back home on only a dollar.

You can’t drive that cheaply. More importantly, driving robs you of exercise, contemplative time and contact with the outside world, all of which I find to be essential as I age. For those who balk, who say they don’t have time to ride a bus or train, who claim that driving is simply faster and more convenient, I agree with you. It’s why almost 92% of all households in America have at least one vehicle (the most popular being some type of truck).

But consider the following reasons — beyond the obvious value to our warming climate — why active transportation will help sustain you in body, mind and spirit.

No. 1: You exercise more.

I spent a total of $4 the other day riding the bus to and from my volunteer gig at Planned Parenthood North Central States (Route 63 there and 87 back) and then to the iconic Riverview Theater in Minneapolis to see the Oscar-winning “Anora” (don’t bother) with a friend (Route 21).

One route is half a mile from my house, the other five blocks and the third barely two blocks. I’d have saved 60 to 90 minutes of travel time had I driven. But I’d have walked far fewer steps than the 15,000 I amassed that day, and I would have missed the chance to really see my city: to greet people on the sidewalk, chat with a bus driver, notice the colorful murals on the sides of old buildings. To be present in a way you can’t be in a car.

Half of all Americans fail to get the recommended 30 minutes a day of physical activity, according to the National Library of Medicine, and those numbers decrease for both aerobic and muscle-strengthening exercises as women and men age. Using transit can help, because it invariably involves walking: to and from the stops and, in my case, to the next stop — or the one beyond that — if the bus or train is running late.

No. 2: You forge your independence.

My husband and I deliver Meals on Wheels every Friday, and we see plenty of old people who no longer have the physical capability to leave their apartment without assistance.

I remember this well with my own parents: Mom eventually was confined to a room, and my dad, though never wheelchair-bound, gradually lost the ability to pursue the activities he enjoyed, including jogging, golfing, skiing and even walking outdoors. Much as I fear losing my mobility, I recognize the time will come when I no longer can stride to the train station or run to a waiting bus.

That’s why I am grateful to be able to use mass transit now. It keeps me healthy and helps me feel part of the world at an age — post-career — when people’s worlds start to shrink. I feel more independent the less I rely on a car, and I get to meet people I otherwise might not encounter, including the folks I chatted with (below) during opening day festivities for the Gold Line bus rapid transit that now serves downtown St. Paul and the eastern suburbs.

No. 3: You engage with the elements

Why live in Minnesota if you shrink from each season’s particular joys and challenges? Earlier this year, on the coldest day of winter, the dental receptionist and mammogram technician were astonished that I had bused to my healthcare appointments. I was equally mystified why they would scrape their windshields and drive on icy roads.

To prove my point, I drew up a list of practical tips for riding mass transit, whether the weather is below zero or cresting 100 degrees. Chief among them: Learn the tools to plan your travel. (ProTip: The Transit app is great!)

- Exchange mobile numbers with whomever you will be meeting. Buses and trains, at least in my town, often run slightly off schedule.

- Protect yourself from crime by investing in a sturdy backpack so you can walk with your arms free and keep valuables out of sight. I’ve been annoyed by loud music and occasional public drinking on a bus, but no one has ever threatened me. The light-rail trains can be intimidating to ride, with less access to a driver. But Metro Transit has reduced trains to two cars — removing the middle car, where drug use was often visible — and begun employing trip agents who check fares and provide a reassuring unarmed presence.

- Pack a water bottle, Kleenex (especially useful in cold temperatures) and sunscreen, important in any season. An extra hat or scarf during the winter and a bill cap to shield your face from summer sun are also useful.

- Catch up on your reading. I often stuff newspapers inside my backpack, and I read my digital subscription for the New York Times or a book I’ve downloaded on my iPhone.

No. 4: You get to practice patience.

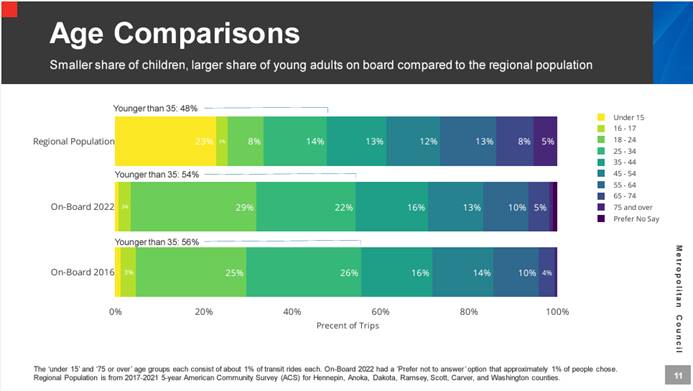

Transit ridership falls off after age 55, according to Metro Transit research, and is miniscule for people 75 and older. But that 20-year window is a time when many of us, if we’re lucky, still have relatively good health. Kandaras, the general manager, hasn’t researched the question of why seniors stop riding transit, “but we want to make it more attractive to adults who are older,” she says.

I can think of several incentives to get my peers out of their vehicles:

- The reality that driving gets harder as your reaction time slows, and people seem to be driving ever faster these days.

- It feels good not to be contributing to the carbon emissions that are killing our planet. In fact, says Kandaras, one group of older adults “said to hit home with climate.”

- Mass transit is more calming than driving. You can read, or just watch the world go by.

That last reason is the most compelling for me. After an adult lifetime of pushing, achieving, trying to live up to expectations, doing what, in hindsight, feels like too much — likely because I no longer can multitask — I appreciate the chance to sit back and relax while I get where I need to go.

“Leave the driving to us,” the old Greyhound Lines slogan said. It was coined in 1956, the year before I was born, when the U.S. automobile market was starting to boom. Turns out, the slogan was meant to woo people who had the option to drive, which is exactly what transit agencies must do if they want to return to pre-pandemic ridership levels.

Mass transit will never win in an argument about convenience, especially among middle-class people who own a car and, therefore, have choices. But peace of mind? Any of us, at any age, could use more of that.