Returning home from a dog walk on a bitterly cold Monday afternoon in mid-January, I saw a black GMC pickup truck idling alongside my house in St. Paul. ICE protestor Renée Macklin Good, a mother and poet, already was dead at the hands of the federal government’s armed invaders in Minnesota. We didn’t know yet that multiple agents would kill intensive care nurse Alex Pretti 17 days later — a murder that my younger son accurately described as an execution. In hindsight, we might have predicted it.

I was on edge that chilly day, my scattered thoughts seeking refuge in quotes about how courage means acting in the face of fear.

I paused on the sidewalk, looked over the enormous slush-sprayed truck and eyed the driver with visible disdain. He immediately rolled down the passenger side window and assured me that he was helping to install new windows at a house down the block. Then he jumped out of the vehicle waving his business card to prove he was a sales consultant with Renewal by Andersen windows and not one of those “jokers” grabbing Hispanic, Somali and Hmong residents off the streets, from their workplaces and out of their homes.

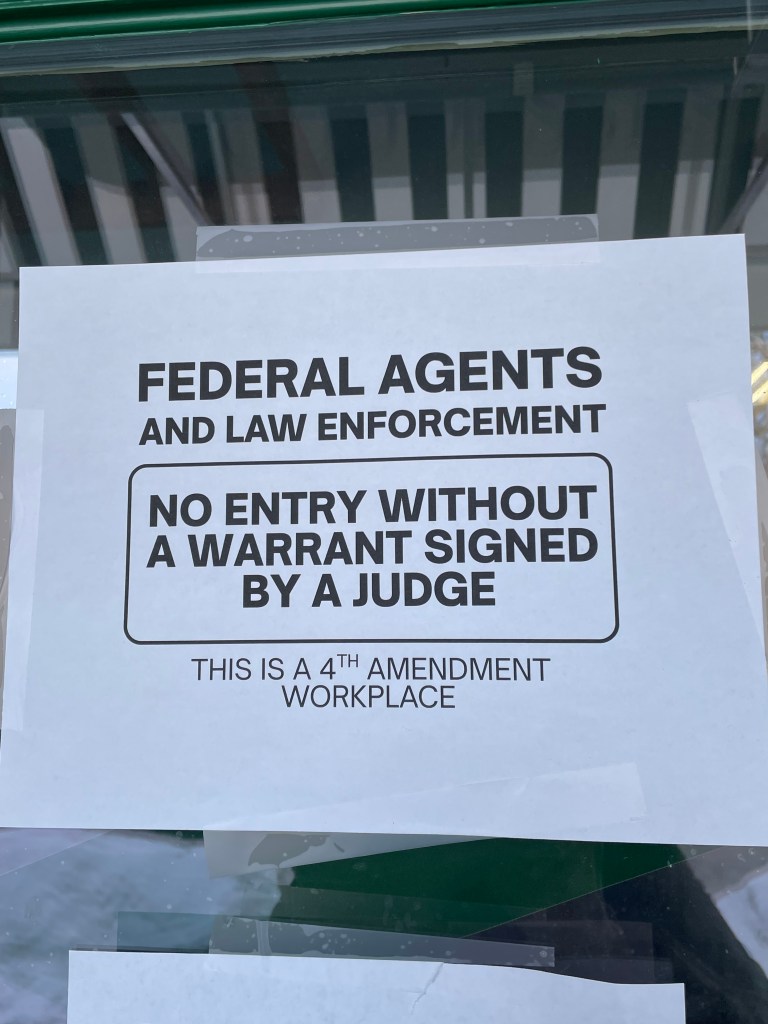

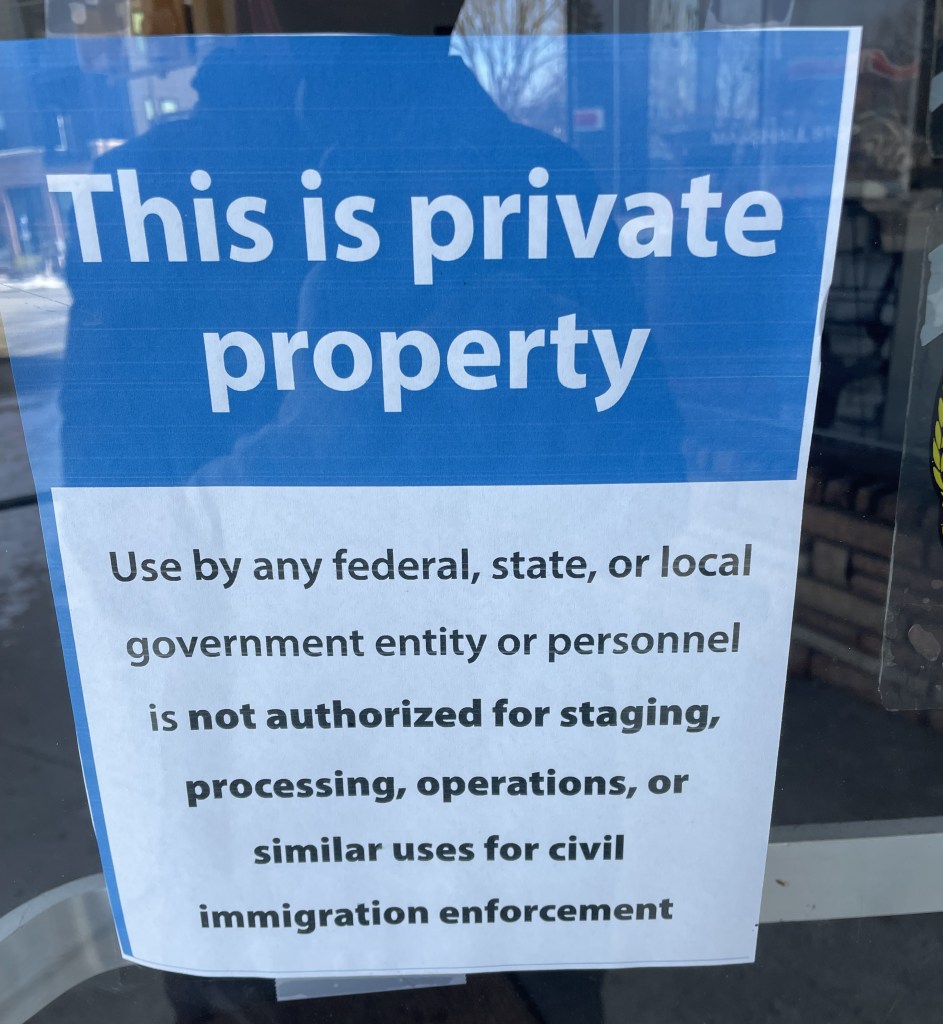

I took the man’s card and apologized for my suspicion, although I didn’t feel sorry for a level of caution that has become commonplace in the Twin Cities since masked and armed Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection agents descended on us in December. “If I ever need new windows,” I told him, “I’ll look you up.”

As I returned to my comfortable, warm home in a middle-class, largely white neighborhood that had not yet witnessed any ICE activity, I thought of a sign I had seen at a protest less than a mile away. “What the government is doing to others, it will eventually do to you,” it read. I can refuse to believe that, or I can get myself prepared.

“No one is coming to save us,” said an organizer from Unidos, a community leadership and empowerment organization, on a Zoom call for some 300 activists in the Twin Cities on January 29. “Only we can save ourselves.”

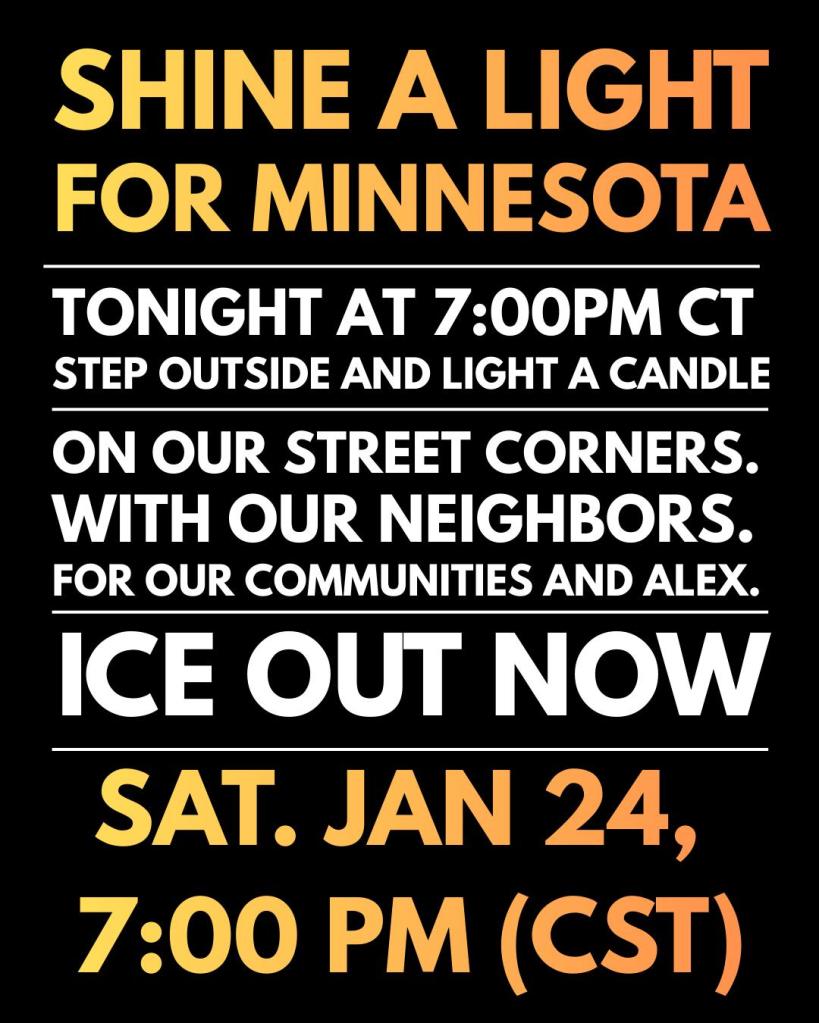

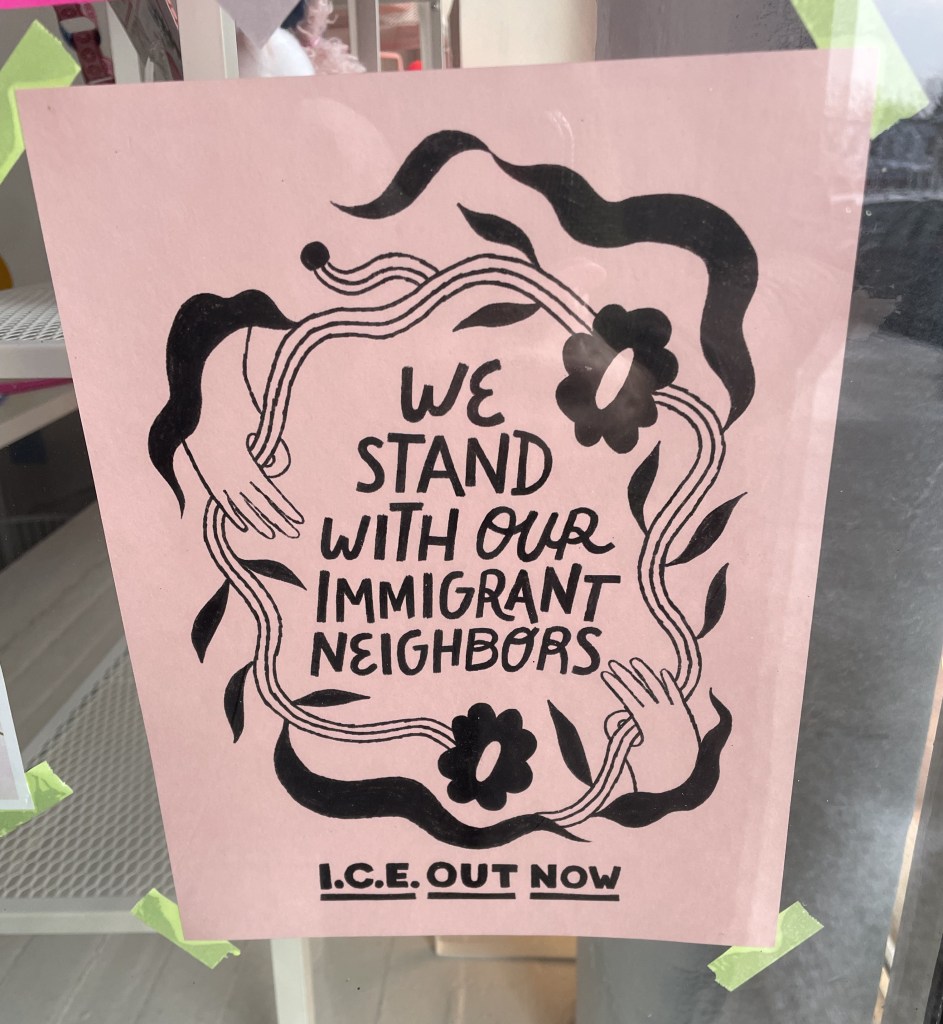

Nearly two months into Operation Metro Surge, ICE has injected terror and uncertainty into our daily lives. Make no mistake, however: People in the Twin Cities and smaller communities that have been targeted throughout the state are bent but not broken. As was demonstrated in Shine a Light for Minnesota the night Alex Pretti was killed, a hastily assembled initiative to get folks out of their homes with a flashlight or candle to commiserate and reconnect, the historically white population has pulled together for all our neighbors, of all colors and ethnicities.

In an Atlantic article headlined “Minnesota Proved MAGA Wrong,” staff writer Adam Serwer calls it “neighborism.” (Shout out to my Saint Paul City Councilmember, Molly Coleman, for pointing her followers to that piece on Bluesky.)

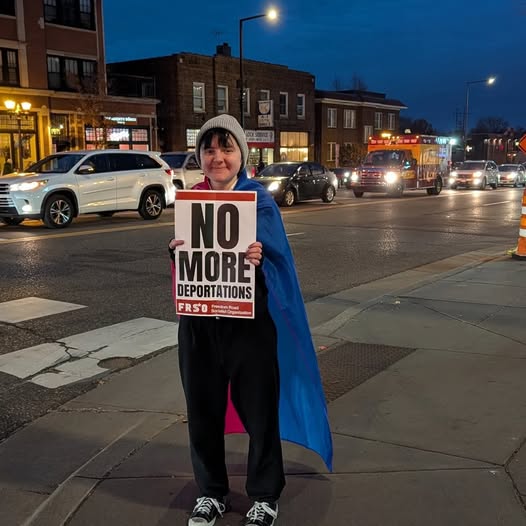

Looking beyond the well-meaning but ultimately meaningless “thoughts and prayers,” many of us who still feel relatively safe are seeking out concrete actions we can take. Signal chat groups have become a private way to organize laundry brigades, school patrols, food delivery for populations afraid to leave their homes and mutual aid initiatives to drive people of color to and from their jobs.

“We are aching from the consistent and unfathomable violence done by ICE to our communities over the last days, weeks and months,” wrote Our Justice, a reproductive freedom organization, in its appeal to leave donations of diapers, pull-ups and feminine pads at Moon Palace Books. An activist bookseller, Moon Palace was the first business in Minneapolis that I saw spray-painted with “Abolish the Police” after officers killed George Floyd in May 2020.

The website Stand with Minnesota highlights countless ways to contribute. And, as my aging peers and I acknowledge, no one person can do it all. “My volunteerism hours are about maxed out,” I told a young compatriot seeking my participation in yet another worthy cause.

I didn’t get to the peaceful mass protest on Friday, January 23 — the Day of Truth and Freedom that saw many schools and offices closed and businesses shuttered in solidarity with courageous resisters (a word that some prefer to “protesters”). Thousands of people filled the streets of downtown Minneapolis, culminating in a rally at Target Center, an event that Target Corp. itself reportedly took no hand in supporting.

Instead, I rode the Green Line to a tiny protest at the State Capitol the next day, feeling the shockwaves as another murder shook the city. I was there as a favor to a colleague. I was there as a favor to myself. After spending several hours with my 6-month-old grandson, I wanted to do something to ensure our democracy holds for his lifetime. Despite our small numbers in the subzero windchill, we thrilled to the waves and honks from passing vehicles as people acknowledged our good intentions and homemade signs.

How, at 68 years old, can I still be so naïve? As though these tragedies, this reign of terror, could never happen in liberal, peaceful Minnesota, a flyover land whose generous support of parks, libraries and other social services has always been a point of pride. I refused to sing or stand for the National Anthem at the Gophers women’s basketball game the day after Pretti’s murder, a perhaps pointless but determined gesture that many social media friends supported. “We have to take action any way we can these days,” one said.

The searing headlines continue to shock me after weeks of these atrocities, and they should: a Black baby and his family being teargassed, a Hmong American man ripped from his house in his underwear, a 5-year-old Hispanic boy and his father deported to Texas, with false and racist claims that the child’s parents had abandoned him.

Earlier in the occupation, my older son directed me to Instagram as a more authentic resource than traditional media for on-the-ground news. I stumbled upon a provocative video by Black musician and author Andre Henry (“fighting despair in the world,” his bio says). “I’m gonna hold your hand while I say this,” he explains. “But if you’re from the U.S., you’ve always lived in a fascist country.”

Employing a gentle tone, Henry seeks to upend the patriotism of white, middle-class, homeowning Baby Boomers raised to believe in the U.S.A. — those of us who benefited from its biases and exclusions, its rules and norms. “What we’re seeing is not America acting like Nazi Germany,” he says, a comparison I have heard from white neighbors — and voiced myself. “It’s America acting like America.”

I recently heard Dr. Yohuru Williams, a Black Civil Rights scholar, speculate on Minnesota Public Radio whether the outrage would be less widespread if the murder victims in Minneapolis had not been white. Another Instagram reel puts this racially charged moment into context for seemingly well-educated whites whose schools taught no lessons on white oppression. “ICE isn’t just like the Gestapo,” says journalist and videographer Ashley B (“history & headlines — decoded, unfiltered”). “They’re closer to slave catchers. And once that clicks, a lot of people get real uncomfortable real fast.”

“Slave patrols are the history that a lot of white families don’t talk about,” she concludes. Mine certainly never did.

The social media posts become exhausting, overwhelming, though they’re also a ready source of information and inspiration. “I was told today by someone close ‘there’s nothing else I can do but pray,’” a former colleague posted. “I call bullsh*t.” Then she asked people to help her list what “we all can do to make a stand against this occupation in our country.”

My advice was this: “Stay connected to your favorite social justice organizations and take their direction. Volunteer at a food shelf like Keystone Community Services, many of which are now delivering groceries to their clients who feel unsafe coming in. Talk to your activist friends for ideas. If we all do what we can, it will be enough.”

It will be, so long as we embrace activism as a way of life, not a job that will be finished once ICE and border agents exit our communities. “This battle is not just to get rid of ICE,” an organizer at the recent Unidos training said. “We are all committed to building the future and the Minnesota that we deserve.”

Having made my living in journalism and communications, I am following a variety of news sources, networking with friends and neighbors, and staying centered in the sharing of information and ideas.

- I love to walk and have volunteered to be a patrol at my neighborhood elementary school, which will begin once I complete my “constitutional observer” training through Monarca on February 1.

- When an ICE agent cased a fourplex that houses University of St. Thomas and Macalester College students three blocks away, I connected a nearby homeowner with the landlord and the university’s chief of staff.

- I told a friend who sings in her church choir about Singing Resistance, which CNN anchor Anderson Cooper covered during his reporting trip to Minneapolis.

“It takes all sorts of people, a variety of personalities and gifts and skills, to make social justice happen,” writes Rev. Shay McKay in the February newsletter for Unity Church-Unitarian in St. Paul.

I recently reviewed the full meaning of the Starfish Theory and recognized that staying stuck in guilt — because, as I grow older, I have less tolerance for the cold and feel unsafe getting to and from nighttime protests — is wasted energy. “Do What You Can” is the title of Rev. McKay’s essay. Anything less is only an excuse and capitulation.