I am drawn to bookstores and concert halls more than to art museums; to music and literature more than so-called fine art.

Still, given that one of my close friends is a longtime docent at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA), I have learned over the years to appreciate paintings, especially, for their micro and macro characteristics — their ability to evoke personal, sometimes painful memories and to illuminate a perspective beyond my own.

More than other visual art forms, paintings inspire me to interrogate my past and present — the skinny girl I was, the old woman I am becoming — and pose questions about a future that already is proving to be more enriching, difficult and diverse than the narrowly white, middle-class, comfortable environment in which I was raised. Paintings inspire me to learn, to stretch and grow. They help me ponder a life that reaches decades back and point me toward an indeterminate amount of time forward.

The Awakening

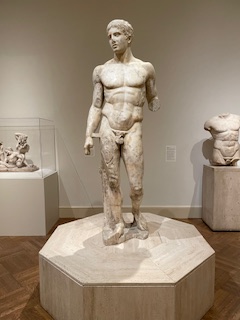

My mother hauled us kids around to museums and the theater when we were sometimes too young to appreciate or comprehend the experience. She figured the exposure would be good for us; plus, being a native of Chicago, she yearned always to escape our small town. I did a version of that awakening in 2007 with my younger son, Nate, when he turned 12, arranging with my docent friend, David Fortney, then in training for his role, to conduct a tour of the art institute for 12-year-old boys.

Imagine our surprise (not) when the tour began with a naked male statue, Doryphoros (Roman, 1st century BE), muscled and marbled but missing a left forearm. Other highlights of the tour included surprisingly small battle armor (how our species has grown!) and MIA’s post-World War II Tatra T87 from the Czech Republic, a luxury car designed in 1936 whose front end resembles the earliest Volkswagen Beetle.

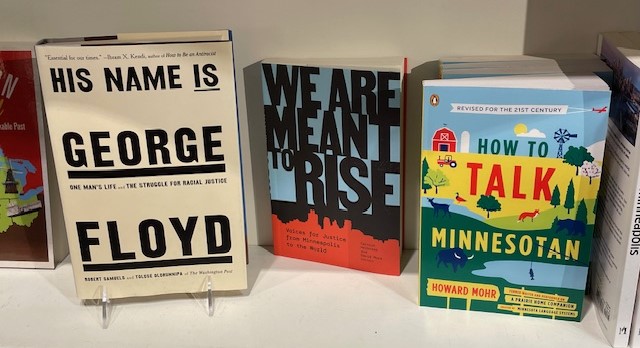

These days, I notice how much more diverse the Minneapolis Institute of Art has become, from the offerings in its bookstore and the ages and ethnicities of its clientele to the artwork displayed in its hushed, white-walled galleries.

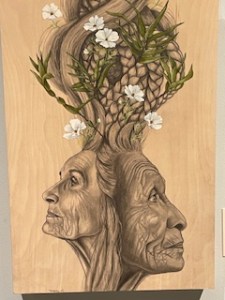

I was introduced to Indigenous artwork in a variety of media through my friend’s book tours, which MIA hosts monthly, of The Night Watchman by Louise Erdrich (Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2021) and Horse by Geraldine Brooks (a favorite of mine this year).

That long-ago museum tour for 12-year-olds left an impression on my son, now 28, because he joins me on these book tours, self-designed by each guide. Widely read in many genres and cultures, Nate has encouraged me to move beyond books about racism and the Black experience (White Fragility, So You Want to Talk About Race, How to Be an Antiracist) and instead read fiction by Blacks and other people of color. That has me currently working through the lyrical, unpunctuated prose and contemporary Black British references of the novel Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo (winner of the Booker Prize in 2019).

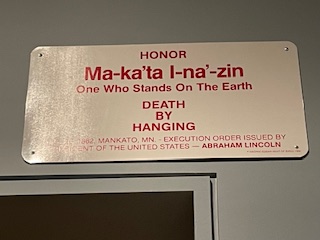

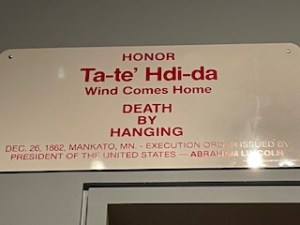

Lately, it is Indigenous lives and cultures that I want to explore, perhaps because I am from the town where 38 Dakota men were hanged, in the presence of their families, on December 26, 1862. When I was in school in Mankato during the 1960s and early 1970s, we learned nothing about the mass execution, lessened by three dozen pardons but ultimately approved — the order issued — by Abraham Lincoln, the president we herald as the “great emancipator.”

A Dog’s Life

My childhood family always had pets — dogs, specifically — and my husband and I continued the tradition with our own sons. Pixie, Gretchen, Skip, Lucy: Those beloved family members came to a humane and sad but dignified end until Griffin, the miniature schnauzer my husband adored and carried around on his shoulder as a puppy. My husband, David, called Griffin his grandchild (we still don’t have one), sometimes telling acquaintances at the dog park, “I’m surprised I don’t sit at home and knit him sweaters.”

Griffin was killed at age 6 in November 2018, hit by a car outside a rural house we were renting in my hometown to attend my stepmother’s funeral. The dog was killed instantly, from what we could discern, with no visible damage or blood on his body. “He died immediately, and we found him,” I tried to reassure my husband. To no avail.

David cried — shuddering, back-heaving sobs — as our older son dug a hole in the frozen dirt of our backyard. Then they wrapped Griffin in a sheet and laid him to rest in the cold ground while I watched from the kitchen window.

You can’t replace a “heart dog,” my sister Penny likes to say. But only a month later, I convinced David to adopt a puppy from Standing Rock in the Dakotas, via a neighbor who rehomes dogs from Indian reservations. Gabby is an athlete, a wary and sometimes standoffish girl who barks at any person, dog or school bus that dares to venture down our side street.

She looks like a smaller, tamer, better-fed version of a dog I saw pictured in the Raphael Begay photo Rez-Dog (2017) at MIA’s special exhibition “In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to Now.”

“This is a post-butchering celebration and gathering with my family at my late grandmother’s home,” the artist wrote in the statement hanging alongside the photo. “There, I saw this dog dragging a sheep’s head that we left outside. . . . I look at it in the same light as how we treat our unsheltered relatives. There’s this sense of concern, empathy, but there is a lack of responsibility or commitment to help.”

Women’s (R)evolution

The last several times I have visited the Minneapolis Institute of Art, I have returned again and again to a portrait on the third floor of a stern, stylish woman sitting upright in a chair, her face turned to the artist — almost daring him to objectify her.

It stands in stark contrast to the reclining nudes and bare-breasted ogling of traditional, centuries old western European art, which grows tiresome for me in the way that its countervailing fascination with royal propriety and the ruling classes turns off my older son, Sam, a Democratic-Socialist.

The painting that speaks to me is Temma in Orange Dress (1975) by Leland Bell, one of several portraits of his daughter by the largely self-taught painter. I perceive it less as a father’s flattering gaze than a reflection of women’s emerging independence — two years after the U.S. Supreme Court passed Roe v. Wade in a 7–2 vote (inconceivable today) and at a time when women’s labor force participation rate exceeded 46 percent, more than 10 points higher than in 1965, a decade earlier.

Unlike the uncertainty and timidity of Christy White (1958) by the feminist portrait artist Alice Neel, which hangs nearby, Temma projects strength. To me, she reads as a career woman, who pursues her own identity and financial means.

When I showed “Temma” to my younger son, I told him the painting reflects my career-woman phase. “Oh, you mean the 40-year phase?” he shot back. And yet much as my sons have seen me, and I have wanted to see myself, as Temma — fierce and forceful, a woman to be reckoned with — at heart I am more “Christy White.” Fearful, insecure, wrestling to this day with whether I walked the right path in a society that forces women to make hard and heartrending choices.

I walked up to “The Barn,” a 1954 painting by Wisconsin artist John Wilde, to see the rendering of a naked woman breaking free, and then a guard pointed out the face of a man watching in the lower left-hand window, a child’s wagon on the ground nearby. Some time later, I came upon a color-soaked painting, “Think Long, Think Wrong” by Avis Charley, of a fashionably clothed Native woman waiting in the sunshine for a bus.

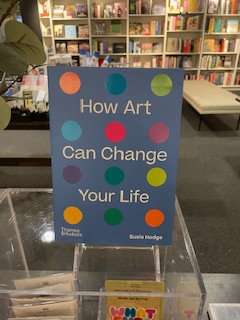

“I create images that I wish I would have seen growing up,” said the artist’s statement. This painting, she explained, “is about putting aside distractions and staying present.” Aside from the art itself, that’s the beauty of an art museum: It helps us reflect upon our lives and values in a calm, quiet place, and assemble disparate images into a cohesive whole.